Videonamics Digital Camera Lens Buying Guide gives you clear, practical advice on choosing the right lens for your digital camera. It explains focal length, aperture, image stabilization, sensor format and lens mounts, and highlights popular lens types such as standard and telephoto zooms, superzooms, wide-angle zooms, macro lenses, fast primes and pancake lenses.

You’ll also find straightforward explanations of focus systems—autofocus, electronic manual focus, manual focus override and fully manual lenses—and why build quality and weather sealing can be important. By the end you’ll better understand your needs and know how to research lenses from brands like Nikon, Canon, Sigma, Tokina, Tamron and Rokinon before making a purchase.

This image is property of i.ytimg.com.

Lens Fundamentals

You should think of a camera lens as the quiet architect of every photograph you make: a stack of glass and metal that gathers light and bends it precisely onto your camera’s sensor to create an image. The way the lens shapes, focuses and transmits light determines sharpness, distortion, contrast and how the world in front of you will feel once flattened into pixels. You don’t need to memorize glass prescriptions, but you do need to understand that the lens is the part of your kit that most directly sculpts the look of your pictures.

What a camera lens is and how it forms images

A lens forms an image by refracting light rays so they converge onto the sensor plane; when those rays meet in focus they recreate a small, inverted version of the scene. Inside a lens are groups of elements arranged to correct optical imperfections and control how light travels. When you adjust focus or aperture, you’re changing geometry: moving elements or narrowing a diaphragm. Knowing this helps you appreciate why lenses feel different, why some focus quietly and others with a mechanical clunk, and why different lenses render the same scene in subtly different emotional ways.

Understanding focal length at a basic level

Focal length is the single number you’ll see most often—like 35mm or 200mm—and it’s shorthand for how “zoomed in” a lens makes the scene appear and how much of the scene it captures. Short focal lengths (wide angles) include more of the scene and exaggerate perspective; long focal lengths (telephotos) compress distances and bring distant subjects closer. It’s not mystical: focal length is a physical distance inside the lens that defines image magnification and angle of view, and learning to read those numbers changes how you compose.

What aperture does and how it affects exposure

Aperture is the adjustable opening in the lens that controls how much light reaches the sensor; it’s expressed as an f-number—f/1.8, f/5.6, f/16—and that one small number speaks to exposure, depth of field and overall image mood. A wider aperture (smaller f-number) lets in more light and gives you a brighter exposure at the same shutter speed, while a narrow aperture reduces light and increases depth of field. Aperture is a creative lever: it affects how luminous and shallow or crisp and detailed your picture feels.

Flange focal distance and why it matters

Flange focal distance is the gap between the rear lens mount and the camera’s sensor plane; it’s a mechanical constant that affects whether a lens can focus to infinity on a particular camera. If the flange distance doesn’t match, you may need an adapter with the correct spacing, and some combinations won’t work at all without optics that degrade image quality. Knowing the flange distance matters when you’re adapting old lenses or mixing brands, because it tells you whether a lens will meet the sensor at the right place to form a sharp image.

Focal Length and Field of View

You’ll choose focal length more than you choose anything else, because it’s the primary decision that determines what you include in the frame and how viewers read spatial relationships. Focal length ties directly to field of view: wider lenses show more, telephoto lenses isolate and compress, and the one you pick will steer the mood of your imagery before you touch exposure or color.

How focal length determines angle of view

Angle of view is simply the slice of the scene your lens can capture, and focal length dictates it: shorter focal lengths widen the angle, longer ones narrow it. That angle interacts with sensor size too, so a 50mm on a full-frame camera looks different than a 50mm on a smaller sensor. You can learn to anticipate how a focal length will make a person appear, how much of a room you’ll get into a frame, or whether a mountain range will feel intimate or distant.

Prime focal lengths versus zoom ranges

Primes have a fixed focal length and often give better optical quality, wider apertures and a lighter build; zooms cover a range, giving you flexibility to reframe without moving your feet. You’ll trade convenience for a little optical compromise with zooms, and trade versatility for a pleasing, often faster rendering with primes. Which you choose usually comes down to whether you prioritize adaptability on the fly or image character and low-light performance.

Crop factor and equivalent focal lengths

Crop factor is the multiplier that relates your camera’s sensor size to a full-frame 35mm reference. On an APS-C sensor, for example, a 50mm lens gives roughly the field of view of a 75–80mm on full frame, because the sensor samples a smaller central portion of the image circle. You need to account for crop when you read a lens spec and when you plan focal lengths for portrait or landscape work, otherwise you’ll be surprised by how tight or wide your images actually are.

Choosing focal lengths for portraits, landscapes, sports and video

For portraits you’ll generally lean toward 85–135mm on full frame for flattering compression and subject isolation; landscapes often benefit from 16–35mm to capture expanses; sports and wildlife demand long reach—200mm and up, often 400mm or more; video needs think about both field of view and movement, so 24–70mm and 35–50mm primes are popular because they let you frame while moving. You should try to match focal length to how you want viewers to feel: intimate, grand, distant, or immersed.

Aperture and Lens Speed

Aperture is where photography meets mood. It’s the control that changes the physical optics of an image and the emotional reading people give it: a shallow depth of field often reads as cinematic and intimate; deep focus can feel clinical or grand. Lens speed—the maximum aperture—determines how readily you can achieve those looks.

f-stop scale and exposure effects

The f-stop scale is logarithmic: each full stop halves or doubles the amount of light. Moving from f/2 to f/4 reduces light by two stops; moving from f/4 to f/2.8 gains one stop. That arithmetic is practical and immediate when you’re balancing ISO and shutter speed. It also explains why lenses with wider maximum apertures (f/1.4, f/1.8) are prized: they let you shoot at lower ISOs and faster shutter speeds in the same light.

Depth of field control and creative separation

Depth of field is the zone of acceptable sharpness in front of and behind your point of focus, and aperture is the main tool for controlling it. A wide aperture will give you a shallow plane, pulling subject and background apart so your subject floats; a narrow aperture brings more of the scene into focus. You’ll use this to emphasize emotion, hide distracting backgrounds, or make architectural details sharp throughout a frame. Depth of field also depends on focal length and subject distance, so all three must be in conversation.

Low-light performance and maximum aperture

A lens with a large maximum aperture is often called a “fast” lens because it lets you use faster shutter speeds for a given scene brightness. That matters when you’re photographing concerts, interiors, or handheld in dim light: a fast lens reduces reliance on high ISO, which can preserve color and reduce noise. If you’re serious about night or indoor shooting, prioritize a lens with a wide maximum aperture—your camera’s sensor matters too, but the lens is the first bottleneck.

Aperture blades, bokeh quality and shape

Bokeh describes the aesthetic quality of out-of-focus areas, and it depends not just on aperture size but on the number and shape of the aperture blades and the optical design. Rounded blades tend to produce smoother, more pleasing circles; many straight blades produce more polygonal highlights when stopped down. You’ll hear reviewers talk about buttery or busy bokeh; when you care about portraiture and subject separation, the character of a lens’s bokeh becomes a deciding factor beyond mere sharpness.

Zoom Lenses Versus Prime Lenses

There’s a practical, almost domestic debate here: zooms are convenient and forgiving; primes can force you into better compositions and often deliver superior optical performance. You’ll want to think about how you like to work—do you move your feet or your lens?—and what compromises you’re willing to accept.

Advantages and trade-offs of zoom lenses

Zooms give you framing flexibility without changing lenses, which matters when subjects move or when you’re in restricted spaces. They’re a single solution for many situations, reducing the need to swap glass. The trade-offs are usually size, weight and sometimes slightly reduced image quality or slower maximum apertures compared with similarly priced primes. Still, modern zooms can be excellent and are often the sensible choice for run-and-gun shooting, events, and travel.

Advantages and trade-offs of prime lenses

Primes typically deliver better sharpness, wider maximum apertures and lighter builds. They can render images with clarity and character that many zooms struggle to match, and they push you to think compositionally because you must move to change framing. The trade-off is convenience: you’re swapping lenses more often and carrying more glass if you want several focal lengths. Primes are rewarding for portrait, low-light and deliberate work where speed and image character matter most.

When a zoom is more practical than a prime

You should reach for a zoom when you need versatility—events, weddings, travel, documentary work—because it’s impractical to keep changing lenses or to carry a set of primes. It’s also more practical when unpredictable distances and fast-changing scenes demand quick reframing. If your priority is getting the shot reliably rather than chasing the last ounce of optical purity, a quality zoom will usually be the sensible choice.

When a prime is the better choice for image quality or speed

You should choose a prime when you need the widest apertures for low-light work or shallow depth of field, or when you want the best possible sharpness and rendering at a given focal length. Portrait shooters, street photographers seeking compactness and cine shooters chasing a particular look often prefer primes. If you care deeply about bokeh quality, micro-contrast and minimal optical compromises, primes will repay you.

Common Lens Types and Their Uses

Lenses are tools for tasks, and matching lens type to photographic intent simplifies choices. There’s no one-size-fits-all; each type excels at particular subjects and poses unique ergonomic and optical trade-offs you should accept consciously.

Standard zooms for everyday shooting

Standard zooms—often 24–70mm or 18–55mm depending on sensor size—are the workhorses you’ll use most: versatile ranges for portraits, landscapes, interiors and casual video. They balance size, weight and optical quality and are ideal if you want a single go-to lens that handles many tasks. A good standard zoom is where you start building habits and discovering what focal lengths you actually use most.

Telephoto and supertelephoto lenses for wildlife and sports

Telephoto lenses bring distant subjects close and isolate them from busy backgrounds, which is essential for sports and wildlife. Supertelephoto glass—300mm, 400mm, 600mm and beyond—requires investment in support gear and often benefits from fast apertures if you want to freeze motion. Choose these lenses when distance is a defining feature of the job; they ask for patience and planning but repay you with images that other equipment simply cannot capture.

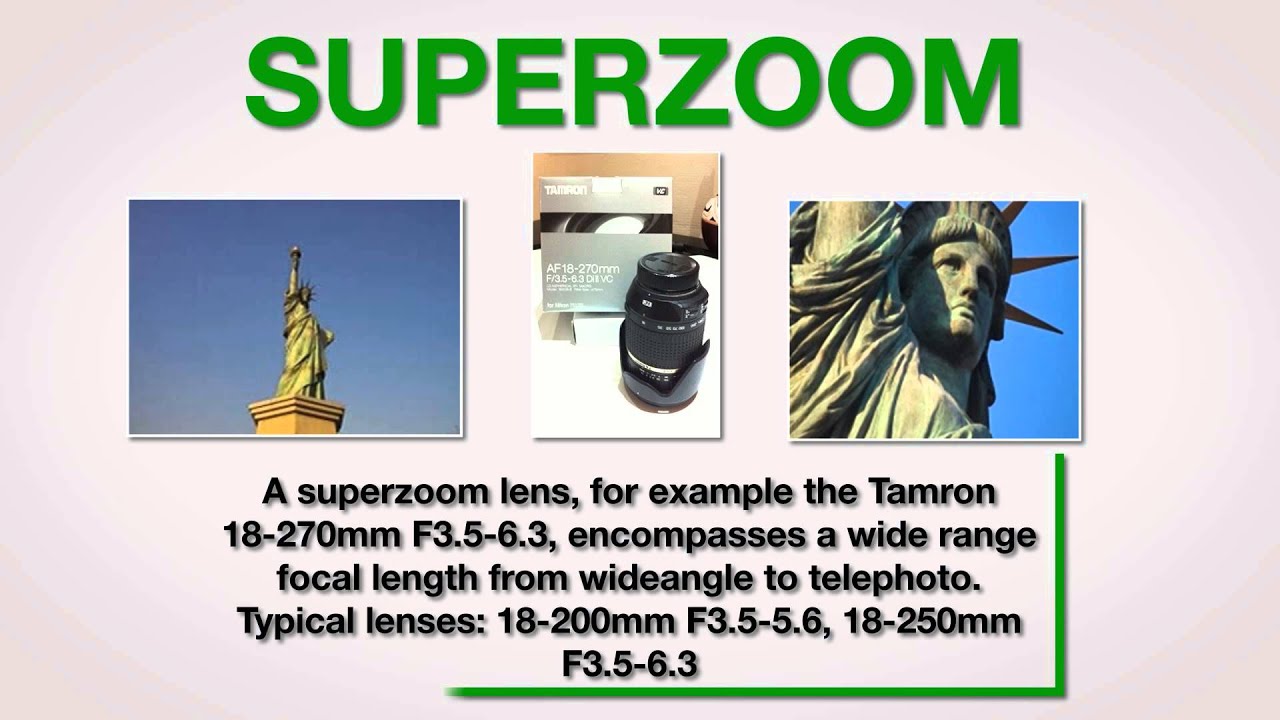

Superzoom lenses for travel and versatility

Superzooms cover extreme ranges like 18–300mm and are popular with travelers who want one-lens convenience. They let you shoot landscapes, portraits and distant subjects without swapping lenses, but they often compromise on maximum aperture and ultimate sharpness. If simplicity, weight savings and packing light are priorities, a superzoom is a practical friend, even if you accept that image quality won’t match specialized glass.

Wide-angle and ultra-wide lenses for landscapes and interiors

Wide and ultra-wide lenses show a lot and emphasize foreground-to-background relationships, which suits landscapes, architecture and interiors. They’ll exaggerate perspective, making nearby objects feel larger and distant planes recede, which can be dramatic or distortive depending on your intent. Use these lenses to create a sense of scale or to include environmental context; they demand attention to composition and often to careful control of distortion.

Macro lenses for close-up detail

Macro lenses are designed to focus extremely close and reproduce subjects at life-size (1:1) or greater magnification. They shine for product, insect and detail work where texture and tiny structures tell the story. Macro shooting changes how you move and light: shallow depth of field, precise focusing and small movements matter. If your practice involves tiny subjects or you love revealing hidden detail, a macro lens becomes a necessary tool.

Fast primes and pancake lenses for portability and low light

Fast primes offer wide apertures, excellent low-light performance and shallow depth of field, while pancake lenses are compact, often with more modest apertures, and prized for portability. You should choose a fast prime when you want cinematic isolation or need to hand-hold in dim situations. Choose a pancake when you value discretion and mobility—street shooters and travelers love them because they make your camera less obtrusive.

Image Stabilization and Vibration Reduction

Image stabilization shifts the calculus of what’s possible handheld. It lets you shoot at slower shutter speeds without blur, which is liberating for low-light and long-lens work. But stabilization is a tool with limits and modes you should learn to use deliberately rather than rely on as a catch-all.

Optical stabilization versus in-body stabilization

Optical stabilization is built into the lens and moves elements to compensate for shake; in-body stabilization (IBIS) shifts the sensor instead. Both reduce blur, but they interact differently with lenses and focal lengths. IBIS is convenient because it works with any mounted lens, including adapted and vintage glass; optical stabilization can be optimized for long telephotos and may communicate with IBIS in modern systems to deliver combined benefits.

How stabilization helps in low light and video

Stabilization allows slower shutter speeds for stills and smoother, less jittery footage for video. For handheld video you’ll notice fewer micro-shakes and a steadier frame; for stills you can drop shutter speed by several stops and keep sharpness when you can’t raise ISO or open aperture further. Stabilization doesn’t replace good technique—your stance, breathing and how you move still matter—but it expands creative options when light is limited.

Stabilization modes and limitations (panning, tripod use)

Stabilization systems have modes for different scenarios: general use, panning where vertical stabilization is reduced, and active modes for video. On a tripod some systems should be turned off because the stabilization mechanism can fight absolute stillness and introduce blur. Panning mode is useful in sports and motorsport because it preserves deliberate horizontal motion while stabilizing other axes. Know the modes and switch them based on how you’re shooting.

Compatibility considerations with lenses and bodies

Not every stabilization system integrates perfectly across brands and generations. Some lenses include sophisticated optical VR that pairs with specific bodies, while IBIS depends on body firmware and mount support. When you mix third-party lenses or adaptors, expect possible limitations: stabilization may still work, but it may not communicate modes or performance optimally. Check compatibility before you rely on stabilization as a feature.

Autofocus, Manual Focus and Focus Technologies

Focus technology shapes how you interact with subjects and how you feel while shooting. AF systems have matured dramatically, but differences in focus motors, modes and features still matter, especially for fast-moving subjects or demanding video work.

Types of AF motors and naming conventions (USM/STM/HSM/etc.)

Manufacturers use different motor types—ring-type ultrasonic motors, stepper motors and linear motors—often branded with initials like USM, STM, HSM. Ring USM motors are fast and precise, good for action; STM and linear motors are quieter and smoother, preferred for video and live focusing. You’ll choose based on whether speed or quiet smoothness matters more for your work: weddings, wildlife, or cinematic video each prefer different AF character.

Single, continuous and hybrid AF modes

Single AF locks focus once and is good for static subjects; continuous AF tracks moving subjects, adjusting focus as they move; hybrid modes blend phase-detection and contrast-detection for faster and more reliable results. For portraits you might use single AF; for sports or kids you’ll prefer continuous AF. Hybrid systems are increasingly effective in handling edge cases, but learning how your camera switches targets and how to use focus points remains crucial.

Manual focus, manual focus override and electronic manual focus

Manual focus gives tactile control when autofocus fails or when you want precision, especially for macro and low-light work. Many modern lenses offer manual focus override, letting you nudge focus without switching modes—this is useful for fine adjustments. Electronic manual focus provides focus-by-wire, which can feel different because the ring doesn’t mechanically move the elements; it’s often programmable and useful in video, but has a different tactile feedback you’ll need to learn.

Video-focused focus features: linear motors, smoothness and focus breathing

For video, focus smoothness and minimal focus breathing (apparent focal length change while focusing) are essential. Linear motors and specially tuned AF systems produce silent, smooth transitions that look professional; cine-style lenses minimize focus breathing and have geared rings for follow-focus systems. If you plan to shoot a lot of video, prioritize lenses with gentle focus throw and consistent optics rather than those optimized solely for stills.

Lens Mounts and Compatibility

Mount choice locks you into ecosystems, at least partially, and affects the lenses you can buy, adapt and use. Mounts dictate mechanical fit and electronic communication, so understanding compatibility prevents awkward surprises when you buy new glass.

Common mount systems and why mount matters

Major brands have distinct mounts—each with different flange distances, electronic contacts and native lens ecosystems. The mount matters because it determines which lenses fit natively, how well features like autofocus and stabilization work, and how many third-party options are available. If you already own bodies or plan a long-term system, prioritize mount compatibility to keep future purchases simpler and more cost-effective.

Using adapters: advantages and drawbacks

Adapters let you put lenses from one mount onto another, expanding options and letting you use classic glass. The advantages are creative and economical; the drawbacks are potential loss of AF, stabilization, or full electronic control, depending on the adapter. Some adaptive lenses include optics to maintain infinity focus, but these can affect image quality. Use adapters deliberately—know what you gain and what you might lose.

Native versus third-party lens compatibility

Third-party manufacturers provide many compatible lenses, often at attractive price points, but compatibility can vary by camera and firmware. Native lenses typically offer the most reliable integration for autofocus, stabilization and metadata, while third-party options can be excellent cost-effective alternatives. When choosing third-party glass, research real-world reports on compatibility with your specific body model rather than assuming universal performance.

Electronic communication: aperture control and EXIF

Modern lenses and bodies communicate aperture, focus distance, focal length and other metadata over electronic contacts, which enables in-camera exposure control, accurate EXIF records and features like lens-based corrections. If you use fully mechanical or adapted lenses, you may lose this nicety and have to enter details manually for some workflows. Electronic communication makes life smoother, so if you want hands-off compatibility prioritize lenses and bodies that talk to each other.

Sensor Formats and Lens Coverage

Sensor size isn’t just a spec on a page: it changes how lenses behave, how much of a scene you capture and even the depth of field at a given aperture. Lenses are designed to project an image circle large enough for certain sensor formats, and choosing the right lens for your sensor matters more than you might expect.

Full-frame, APS-C, Micro Four Thirds differences

Full-frame sensors match the old 35mm standard and give wider fields of view and shallower depth of field for a given focal length and aperture. APS-C sensors crop the image, narrowing the field of view and increasing perceived focal length; Micro Four Thirds crops more, which benefits reach but sacrifices background separation. Each format has trade-offs in noise performance, lens size and depth-of-field control; your preference will shape whether you favor large sensors and glass or compact systems.

How sensor size affects field of view and depth of field

Smaller sensors narrow field of view for the same focal length, which is why crop factors exist. They also increase depth of field at equivalent apertures, making it harder to get that creamy background blur with shorter lenses. If you crave shallow depth of field and low-light performance, larger sensors help; if you want reach and small camera size, smaller sensors are compelling. Understand these relationships so you can match lenses to the visual outcomes you want.

Lens formats (full-frame vs crop-specific lenses) and vignetting

Some lenses are designed for smaller sensors and don’t project a large enough image circle for full-frame sensors; using a crop-specific lens on a larger sensor causes vignetting or dark corners. Conversely, full-frame lenses work on smaller sensors but may be larger and heavier than necessary. Choose lenses that cover your sensor format to avoid unexpected vignetting and to get optimal performance across the frame.

Choosing lenses that cover your camera’s sensor

When shopping, confirm the lens’s intended format against your sensor. If you move between formats you might prefer full-frame lenses for future-proofing, but if weight and cost are concerns, crop-specific lenses can be perfectly sensible. Thinking ahead about upgrades matters: investing in lenses that suit your possible future bodies can save money and hassle.

Conclusion

By now you should feel like you can look at a lens spec sheet and understand the decisions it implies. A lens is a mixture of mechanical design, optical trade-offs and ecosystem compatibility—so you’re not just buying glass, you’re buying a set of creative possibilities and limitations.

Key factors to weigh: focal length, aperture, mount and stabilization

When choosing, weigh focal length for framing, maximum aperture for low light and creative control, mount compatibility for future-proofing, and stabilization for practical hand-held use. Consider size, weight, and whether you need autofocus performance for fast action. Prioritize the factors that align with the subjects you shoot most often; that clarity will make choices feel less arbitrary.

Checklist to use before making a lens purchase

Before you buy, confirm the lens covers your sensor, check mount compatibility and stabilization behavior with your body, consider the maximum aperture you’ll realistically use, and think about the lens’s size and weight for your workflow. Read real-world tests for autofocus and bokeh character, and decide whether a zoom or a prime better serves your shooting habits. This small checklist prevents buyer’s remorse.

Next steps: test, rent or compare samples for your camera

If you can, try lenses on your camera body before committing—renting or borrowing is a low-risk way to see how a lens handles and renders on your system. Compare sample images at the apertures and focal lengths you’ll use most, and notice ergonomics: does the focus ring feel right, is the weight manageable, does the autofocus behave reliably? Empirical experience will tell you more than specs alone.

Where to learn more and reliable resources (reviews, Videonamics)

Keep learning by reading thoughtful reviews, watching hands-on demonstrations and comparing real-world sample images on platforms that explain compatibility and performance clearly. Videonamics offers a practical, buyer-focused overview of lens types and features which can help you shape your shortlist. The more you engage—test, compare, ask—you’ll find that lens buying becomes less opaque and more like choosing a companion for the kind of pictures you want to make.